Picture it: Angers, France, July 4, 2017. I've traveled across the Atlantic Ocean to talk to an international (but mostly European) audience about guns in America. As my presentation wore on, their expressions became more and more distorted, twisting into grimaces of disbelief and confusion. It was both patriotic and deeply embarrassing.

The CDC, NIH, and other government research agencies are prohibited from examining gun violence by the 1996 Dickey Amendment. However, they do make firearm mortality data available through the CDC mortality files. Any epidemiology on guns must be performed by private citizens. So, here we are.

The original presentation covered both homicide and suicide. I'm happy to talk about homicide at a different time, but today let's just look at the suicide side of things.

Half of completed suicides are gun suicides. The rest mostly die by suffocation or poison. Cutting, though romantic, is rarely an effective way to complete suicide. Guns are going to be the quickest, easiest, and most effective way for a person to end their life. That's a problem. The majority of people who attempt suicide once (and fail) will never try again. But there's no second chance with a gun.

On the other hand, nearly two-thirds of the firearm deaths in the United States are suicide. We rarely hear about this in the news chatter. Thirty-six percent are homicide, 2% accidental, and 1% "legal" (a category including both deployed military casualties and people killed by police). You are twice as likely to die by shooting yourself than by getting shot by someone else (this varies by race and gender).

|

| Suicide rates over time. The y-axis is suicide rate per 100,000 population. |

The graph above shows suicide trends since 1970, though I am typically skeptical of numbers before 1999. If we only consider suicide rates from 2000 to 2015, it's clear there has been a significant increase. In fact, the national suicide rate (age 15+) was 13.2 in 1999 and 17.0 in 2016. That's an increase of 29% in less than 20 years. Until recently, firearm suicides outnumbered non-firearm suicides. Both are increasing, but non-firearm suicide is increasing more rapidly.

|

| Suicide rates by age. The y-axis is rate per 100,000 population. |

How people kill themselves changes depending on who they are. One factor is age. Younger people are more likely to use non-gun means, but this trend falls off after age 54. Older suicides are much more likely to be firearm related.

|

| Race/ethnicity, guns, and suicide. The y-axis is rate per 100,000. AIAN=American Indian/Alaska Native. API=Asian/Pacific Islander. White- White, non-Hispanic. |

The figure above shows that only non-Hispanic whites are more likely to use guns than other means. American Indians/Alaska Natives (AIAN), Hispanics, and Asian/Pacific Islanders are the opposite. We'll talk more about race, ethnicity, and suicide in a different post (probably many posts), but non-Hispanic white and AIAN are the two groups at highest suicide risk. It's significant that they behave so differently.

|

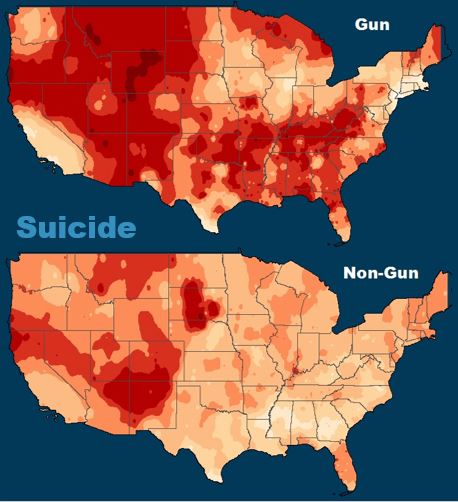

| Smoothed suicide rates, 1999-2015. The legend is missing, but both maps are on the same scale so they can be directly compared. |

The map above shows how the preponderance of gun and non-gun suicide changes over space. Gun suicide is highest in the mountains, from the Rockies and Basin and Range region, through the Ozarks and the Appalachians. The South has much higher rates of gun suicide than the mid-Atlantic or the upper Midwest. The California bubble is clearly visible on both maps, while the middle West Coast, caught between San Francisco and Portland, is struggling. Low rates in South Texas highlight the Hispanic Paradox.

Meanwhile, the rates of non-firearm suicide are typically more evenly distributed, except for a few spots in the Southwest and the upper Great Plains. These areas mostly align with the largest reservation populations. In general, New Mexico, Colorado, Montana, and Northern California are the hardest hit, while the BosWash region is the least vulnerable.

|

| Urbanization and Suicide. The y-axis is rate per 100,000 population. |

The urbanization chart shows how the means of suicide change when moving from urban to rural parts of the US. In large metro regions, non-gun suicide dominates, but that pattern reverses quickly. Non-gun suicide is pretty much even across all types of urbanization. However, gun suicide nearly triples moving from large central metro to non-core areas.

Remember, this is just data on completed suicide; I don't have good numbers for attempted suicide. It is possible that attempts are no more frequent in rural areas than urban, it's just that strapped rural people are more likely to get the job done, so to speak. Or, it could be possible that people in rural areas really are that much more likely to feel desperately suicidal. This is one of the riddles we need to work through.

|

| Bear with me, this is the statistics. This is where things get fun! |

I also ran correlations between the suicide rates and some other factors, at the county level. Gun suicide was more common in counties with older populations and low population density, and less likely in counties with high education, high income, and high robbery rates. Non-firearm suicide was less likely where there is a large proportion of black people and high levels of poor education.

Some of these results are intuitive, given what we talked about before with age and race. Some are a surprise (education is hard for me to wrap my head around.) This is the essence of science. We slice this stuff up so we can start trying to explain patterns.

There is so much more to this, but that's why I have this blog. This is just one way of introducing you to what I actually do as an academic researcher. Some posts will be like this, some will be more theoretical, some more personal, and some even more technical. It's all related.

Back to Angers. As I wrapped up my talk, looks of fear and disgust morphed into sadness and sympathy. If you actually look at what's going on, you'll see that our free-for-all gun policy is mostly fueling our own misery and suicide. I don't know how to fix it, I don't have the answers. I do, however, have a realistic set of questions.

I ended my presentation with the line, "Come visit us in America. It's not as scary as you think."

I'm not sure that's true, though.

Comments

Post a Comment